I have a thing for virtual machines that are implemented in the language (or a subset of the language) they are built to execute. If I were in the academia or just had a little bit more free time I would definitely start working on a JavaScript VM written in JavaScript. Actually this would not be a unique project for JavaScript because people from Université de Montréal kinda got there first with Tachyon, but I have some ideas I would like to pursue myself.

I however have another dream closely connected to (meta)circular virtual machines. I want to help JavaScript developers understand how JS engines work. I think understanding the tools you are wielding is of uttermost importance in our trade. The more people would stop seeing JS VM as a mysterious black box that converts JavaScript source into some zeros-and-ones the better.

I however have another dream closely connected to (meta)circular virtual machines. I want to help JavaScript developers understand how JS engines work. I think understanding the tools you are wielding is of uttermost importance in our trade. The more people would stop seeing JS VM as a mysterious black box that converts JavaScript source into some zeros-and-ones the better.

I should say that I am not alone in my desire to explain how things work internally and help people write a more performant code. A lot of people from all over the world are trying to do the same. But there is I think a problem that prevents this knowledge from being absorbed efficiently by developers. We are trying to convey our knowledge in the wrong form. I am guilty of this myself:

I should say that I am not alone in my desire to explain how things work internally and help people write a more performant code. A lot of people from all over the world are trying to do the same. But there is I think a problem that prevents this knowledge from being absorbed efficiently by developers. We are trying to convey our knowledge in the wrong form. I am guilty of this myself:

- sometimes I wrap things I know about V8 into hard to digest lists of "do this, not that" recommendations. The problem with such serving is that it really does not explain anything. Most probably it will be followed like a sacred ritual and might easily become outdated without anybody noticing it.

- sometimes trying to explain how VMs works internally we choose wrong level of abstraction. I love a thought that seeing a slide full of assembly code might encourage people to learn assembly and reread this slide later, but I am afraid that sometimes these slides just fall trough and get forgotten by people as something not useful in practice.

I have been thinking about these problems for quite some time and I decided that it might be worth to try explaining JavaScript VM in JavaScript. The talk "V8 Inside Out" that I've given at WebRebels 2012 pursues exactly this idea [video] [slides] and in this post I would like to revisit things I've been talking about in Oslo but now without any audible obstructions (I like to believe that my way of writing is much less funky than my way of speaking ☺).

Implementing dynamic language in JavaScript

Imagine that you want to implement in JavaScript a VM for a language that is very similar to JavaScript in terms semantics but has a much simpler object model: instead of JS objects it has tables mapping keys of any type to values. For simplicity lets just think about Lua, which is actually both very similar to JavaScript and very different as a language. My favorite "make array of points and then compute vector sum" example would look approximately like this:

function MakePoint(x, y)

local point = {}

point.x = x

point.y = y

return point

end

function MakeArrayOfPoints(N)

local array = {}

local m = -1

for i = 0, N do

m = m * -1

array[i] = MakePoint(m * i, m * -i)

end

array.n = N

return array

end

function SumArrayOfPoints(array)

local sum = MakePoint(0, 0)

for i = 0, array.n do

sum.x = sum.x + array[i].x

sum.y = sum.y + array[i].y

end

return sum

end

function CheckResult(sum)

local x = sum.x

local y = sum.y

if x ~= 50000 or y ~= -50000 then

error("failed: x = " .. x .. ", y = " .. y)

end

end

local N = 100000

local array = MakeArrayOfPoints(N)

local start_ms = os.clock() * 1000;

for i = 0, 5 do

local sum = SumArrayOfPoints(array)

CheckResult(sum)

end

local end_ms = os.clock() * 1000;

print(end_ms - start_ms)Note that I have a habit of checking at least some final results computed by my μbenchmark. This saves me from embarrassment when somebody discovers that my revolutionary jsperf test-cases are nothing but my own bugs.

If you take the code above and put it into Lua interpreter you will get something like this:

∮ lua points.lua 150.2

Good, but does not help to understand how VMs work. So lets think how it could look like if we had quasi-Lua VM written in JavaScript. "Quasi" because I don't want to implement full Lua semantics, I prefer to focus only on the objects are tables aspect of it. Naïve compiler could translate our code down to JavaScript like this:

function MakePoint(x, y) {

var point = new Table();

STORE(point, 'x', x);

STORE(point, 'y', y);

return point;

}

function MakeArrayOfPoints(N) {

var array = new Table();

var m = -1;

for (var i = 0; i <= N; i++) {

m = m * -1;

STORE(array, i, MakePoint(m * i, m * -i));

}

STORE(array, 'n', N);

return array;

}

function SumArrayOfPoints(array) {

var sum = MakePoint(0, 0);

for (var i = 0; i <= LOAD(array, 'n'); i++) {

STORE(sum, 'x', LOAD(sum, 'x') + LOAD(LOAD(array, i), 'x'));

STORE(sum, 'y', LOAD(sum, 'y') + LOAD(LOAD(array, i), 'y'));

}

return sum;

}

function CheckResult(sum) {

var x = LOAD(sum, 'x');

var y = LOAD(sum, 'y');

if (x !== 50000 || y !== -50000) {

throw new Error("failed: x = " + x + ", y = " + y);

}

}

var N = 100000;

var array = MakeArrayOfPoints(N);

var start = LOAD(os, 'clock')() * 1000;

for (var i = 0; i <= 5; i++) {

var sum = SumArrayOfPoints(array);

CheckResult(sum);

}

var end = LOAD(os, 'clock')() * 1000;

print(end - start);However if you just try to run translated code with d8 (V8's standalone shell) it will politely refuse:

∮ d8 points.js

points.js:9: ReferenceError: Table is not defined

var array = new Table();

^

ReferenceError: Table is not defined

at MakeArrayOfPoints (points.js:9:19)

at points.js:37:13

The reason for this refusal is simple: we are still missing runtime system code which is actually responsible for implementing object model and semantics of loads and stores. It might seem obvious, but I want to highlight this: VM, that looks like a single black box from the outside, on the inside is actually an orchestra of boxes playing together to deliver best possible performance. There are compilers, runtime routines, object model, garbage collector, etc. Fortunately our language and example are very simple so our runtime system is only couple dozen lines large:

function Table() {

// Map from ES Harmony is a simple dictionary-style collection.

this.map = new Map;

}

Table.prototype = {

load: function (key) { return this.map.get(key); },

store: function (key, value) { this.map.set(key, value); }

};

function CHECK_TABLE(t) {

if (!(t instanceof Table)) {

throw new Error("table expected");

}

}

function LOAD(t, k) {

CHECK_TABLE(t);

return t.load(k);

}

function STORE(t, k, v) {

CHECK_TABLE(t);

t.store(k, v);

}

var os = new Table();

STORE(os, 'clock', function () {

return Date.now() / 1000;

});Notice that I have to use Harmony Map instead of normal JavaScript Object because potentially table can contain any key, not just string ones.

∮ d8 --harmony quasi-lua-runtime.js points.js 737

Now our translated code works but is disappointingly slow because of all those levels of abstraction every load and store have to cross before they get to the value. Lets try to reduce this overhead by applying the very same fundamental optimization that most JavaScript VMs apply these days: inline caching. Even JS VMs written in Java will eventually use it because

Now our translated code works but is disappointingly slow because of all those levels of abstraction every load and store have to cross before they get to the value. Lets try to reduce this overhead by applying the very same fundamental optimization that most JavaScript VMs apply these days: inline caching. Even JS VMs written in Java will eventually use it because invokedynamic is essentially a structural inline cache exposed at bytecode level. Inline caching (usually abbreviated as IC in V8 sources) is actually a very old technique developed roughly 30 years ago for Smalltalk VMs.

Good duck always quacks the same way

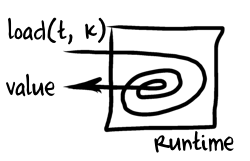

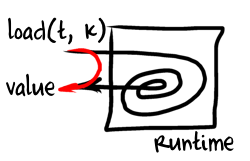

The idea behind inline caching is very simple: we want to create a bypass or fast path that would allow us to quickly, without entering runtime system, load object's property if our assumptions about object and it's properties are correct. It's quite hard to formulate any meaningful assumptions about object layout in a program written in language full of dynamic typing, late binding and other quirks like

The idea behind inline caching is very simple: we want to create a bypass or fast path that would allow us to quickly, without entering runtime system, load object's property if our assumptions about object and it's properties are correct. It's quite hard to formulate any meaningful assumptions about object layout in a program written in language full of dynamic typing, late binding and other quirks like eval so instead we want to let our loads/stores observe&learn: once they see some object they can adapt themselves in a way that makes subsequent loads from similarly structured objects faster. In a sense we are going to cache knowledge about the layout of the previously seen object inside the load/store itself hence the name inline caching. ICs can be actually applied to virtually any operation with a dynamic behavior as long as you can figure out a meaningful fast path: arithmetical operators, calls to free functions, calls to methods, etc. Some ICs can also cache more than a single fast path that is become polymorphic.

If we start thinking how to apply ICs to the translated code above it soon becomes obvious that we need to change our object model. There is no way we can do a fast load from a Map, we always have to go through get method. [If we could peak into raw hashtable behind Map we could make IC work for us even without new object layout by caching bucket index.]

Discovering hidden structure

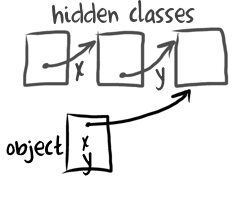

For efficiency tables that are used like structured data should become more like C structs: a sequence of named fields at fixed offsets. The same about tables that are used as arrays: we want numeric properties to be stored in array like fashion. But it's obvious that not every table fits such representation: some are actually used as tables, either contain non-string non-number keys or contain too many string named properties that come and disappear as table is mutated. Unfortunately we can't perform any kind of expensive type inference, instead we have to discover a structure behind each and every table while the program runs creating and mutating them. Fortunately there is a well known technique that allows to do precisely that ☺. This technique is known as hidden classes.

The idea behind hidden classes boils down to two simple things:

- runtime system associates a hidden class with each an every object, just like Java VM would associate an instance of

java.lang.Classwith every object; - if layout of the object changes then runtime system will create or find a new hidden class that matches this new layout and attach it to the object;

Hidden classes have a very important feature: they allow VM to quickly check assumptions about object layout by doing a simple comparison against a cached hidden class. This is exactly what we need for our inline caches. Lets implement some simple hidden classes system for our quasi-Lua runtime. Every hidden class is essentially a collection of property descriptors, where each descriptor is either a real property or a transition that points from a class that does not have some property to a class that has this property:

function Transition(klass) {

this.klass = klass;

}

function Property(index) {

this.index = index;

}

function Klass(kind) {

// Classes are "fast" if they are C-struct like and "slow" is they are Map-like.

this.kind = kind;

this.descriptors = new Map;

this.keys = [];

}Transitions exist to enable sharing of hidden classes between objects that are created in the same way: if you have two objects that share hidden class and you add the same property to both of them you don't want to get different hidden classes.

Klass.prototype = {

// Create hidden class with a new property that does not exist on

// the current hidden class.

addProperty: function (key) {

var klass = this.clone();

klass.append(key);

// Connect hidden classes with transition to enable sharing:

// this == add property key ==> klass

this.descriptors.set(key, new Transition(klass));

return klass;

},

hasProperty: function (key) {

return this.descriptors.has(key);

},

getDescriptor: function (key) {

return this.descriptors.get(key);

},

getIndex: function (key) {

return this.getDescriptor(key).index;

},

// Create clone of this hidden class that has same properties

// at same offsets (but does not have any transitions).

clone: function () {

var klass = new Klass(this.kind);

klass.keys = this.keys.slice(0);

for (var i = 0; i < this.keys.length; i++) {

var key = this.keys[i];

klass.descriptors.set(key, this.descriptors.get(key));

}

return klass;

},

// Add real property to descriptors.

append: function (key) {

this.keys.push(key);

this.descriptors.set(key, new Property(this.keys.length - 1));

}

};Now we can make our tables flexible and allow them to adapt to the way they are constructed

var ROOT_KLASS = new Klass("fast");

function Table() {

// All tables start from the fast empty root hidden class and form

// a single tree. In V8 hidden classes actually form a forest -

// there are multiple root classes, e.g. one for each constructor.

// This is partially due to the fact that hidden classes in V8

// encapsulate constructor specific information, e.g. prototype

// poiinter is actually stored in the hidden class and not in the

// object itself so classes with different prototypes must have

// different hidden classes even if they have the same structure.

// However having multiple root classes also allows to evolve these

// trees separately capturing class specific evolution independently.

this.klass = ROOT_KLASS;

this.properties = []; // Array of named properties: 'x','y',...

this.elements = []; // Array of indexed properties: 0, 1, ...

// We will actually cheat a little bit and allow any int32 to go here,

// we will also allow V8 to select appropriate representation for

// the array's backing store. There are too many details to cover in

// a single blog post :-)

}

Table.prototype = {

load: function (key) {

if (this.klass.kind === "slow") {

// Slow class => properties are represented as Map.

return this.properties.get(key);

}

// This is fast table with indexed and named properties only.

if (typeof key === "number" && (key | 0) === key) { // Indexed property.

return this.elements[key];

} else if (typeof key === "string") { // Named property.

var idx = this.findPropertyForRead(key);

return (idx >= 0) ? this.properties[idx] : void 0;

}

// There can be only string&number keys on fast table.

return void 0;

},

store: function (key, value) {

if (this.klass.kind === "slow") {

// Slow class => properties are represented as Map.

this.properties.set(key, value);

return;

}

// This is fast table with indexed and named properties only.

if (typeof key === "number" && (key | 0) === key) { // Indexed property.

this.elements[key] = value;

return;

} else if (typeof key === "string") { // Named property.

var index = this.findPropertyForWrite(key);

if (index >= 0) {

this.properties[index] = value;

return;

}

}

this.convertToSlow();

this.store(key, value);

},

// Find property or add one if possible, returns property index

// or -1 if we have too many properties and should switch to slow.

findPropertyForWrite: function (key) {

if (!this.klass.hasProperty(key)) { // Try adding property if it does not exist.

// To many properties! Achtung! Fast case kaput.

if (this.klass.keys.length > 20) return -1;

// Switch class to the one that has this property.

this.klass = this.klass.addProperty(key);

return this.klass.getIndex(key);

}

var desc = this.klass.getDescriptor(key);

if (desc instanceof Transition) {

// Property does not exist yet but we have a transition to the class that has it.

this.klass = desc.klass;

return this.klass.getIndex(key);

}

// Get index of existing property.

return desc.index;

},

// Find property index if property exists, return -1 otherwise.

findPropertyForRead: function (key) {

if (!this.klass.hasProperty(key)) return -1;

var desc = this.klass.getDescriptor(key);

if (!(desc instanceof Property)) return -1; // Here we are not interested in transitions.

return desc.index;

},

// Copy all properties into the Map and switch to slow class.

convertToSlow: function () {

var map = new Map;

for (var i = 0; i < this.klass.keys.length; i++) {

var key = this.klass.keys[i];

var val = this.properties[i];

map.set(key, val);

}

Object.keys(this.elements).forEach(function (key) {

var val = this.elements[key];

map.set(key | 0, val); // Funky JS, force key back to int32.

}, this);

this.properties = map;

this.elements = null;

this.klass = new Klass("slow");

}

};[I am not going to explain every line of the code because it's commented JavaScript; not C++ or assembly... This is the whole point of using JavaScript. However you can ask anything unclear in comments or by dropping me a mail]

Now that we have hidden classes in our runtime system that would allow us to perform quick checks of object layout and quick loads of properties by their index we just have to implement inline caches themselves. This requires some additional functionality both in compiler and runtime system (remember how I was talking about cooperation between different parts of VM?).

Patchwork quilts of generated code

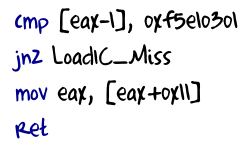

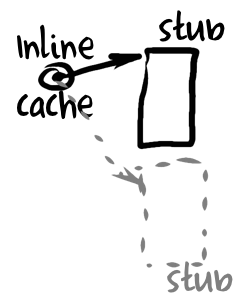

One of many ways to implement an inline cache is to split it into two pieces: modifiable call site in the generated code and a set of stubs (small pieces of generated native code) that can be called from that call site. It is essential that stubs themselves (or runtime system) could find callsite from which they were called: stubs contain only fast paths compiled under certain assumptions, if those assumptions do not apply for an object that stub sees then it can initiate modification (patching) of the call site that invoked this stub to adapt that site for new circumstances. Our pure JavaScript ICs will also consist of two parts:

One of many ways to implement an inline cache is to split it into two pieces: modifiable call site in the generated code and a set of stubs (small pieces of generated native code) that can be called from that call site. It is essential that stubs themselves (or runtime system) could find callsite from which they were called: stubs contain only fast paths compiled under certain assumptions, if those assumptions do not apply for an object that stub sees then it can initiate modification (patching) of the call site that invoked this stub to adapt that site for new circumstances. Our pure JavaScript ICs will also consist of two parts:

- a global variable per IC will be used to emulate modifiable call instruction;

- and closures will be used instead of stubs.

In the native code V8 finds IC sites to patch by inspecting return address sitting on the stack. We can't do anything like that in the pure JavaScript (arguments.caller is not fine-grained enough) so we'll just pass IC's id into IC stub explicitly. Here is how IC-ified code will look like:

// Initially all ICs are in uninitialized state.

// They are not hitting the cache and always missing into runtime system.

var STORE$0 = NAMED_STORE_MISS;

var STORE$1 = NAMED_STORE_MISS;

var KEYED_STORE$2 = KEYED_STORE_MISS;

var STORE$3 = NAMED_STORE_MISS;

var LOAD$4 = NAMED_LOAD_MISS;

var STORE$5 = NAMED_STORE_MISS;

var LOAD$6 = NAMED_LOAD_MISS;

var LOAD$7 = NAMED_LOAD_MISS;

var KEYED_LOAD$8 = KEYED_LOAD_MISS;

var STORE$9 = NAMED_STORE_MISS;

var LOAD$10 = NAMED_LOAD_MISS;

var LOAD$11 = NAMED_LOAD_MISS;

var KEYED_LOAD$12 = KEYED_LOAD_MISS;

var LOAD$13 = NAMED_LOAD_MISS;

var LOAD$14 = NAMED_LOAD_MISS;

function MakePoint(x, y) {

var point = new Table();

STORE$0(point, 'x', x, 0); // The last number is IC's id: STORE$0 ⇒ id is 0

STORE$1(point, 'y', y, 1);

return point;

}

function MakeArrayOfPoints(N) {

var array = new Table();

var m = -1;

for (var i = 0; i <= N; i++) {

m = m * -1;

// Now we are also distinguishing between expressions x[p] and x.p.

// The fist one is called keyed load/store and the second one is called

// named load/store.

// The main difference is that named load/stores use a fixed known

// constant string key and thus can be specialized for a fixed property

// offset.

KEYED_STORE$2(array, i, MakePoint(m * i, m * -i), 2);

}

STORE$3(array, 'n', N, 3);

return array;

}

function SumArrayOfPoints(array) {

var sum = MakePoint(0, 0);

for (var i = 0; i <= LOAD$4(array, 'n', 4); i++) {

STORE$5(sum, 'x', LOAD$6(sum, 'x', 6) + LOAD$7(KEYED_LOAD$8(array, i, 8), 'x', 7), 5);

STORE$9(sum, 'y', LOAD$10(sum, 'y', 10) + LOAD$11(KEYED_LOAD$12(array, i, 12), 'y', 11), 9);

}

return sum;

}

function CheckResults(sum) {

var x = LOAD$13(sum, 'x', 13);

var y = LOAD$14(sum, 'y', 14);

if (x !== 50000 || y !== -50000) throw new Error("failed x: " + x + ", y:" + y);

}Changes above are again self-explanatory: every property load/store site got it's own IC with an id. One small last step left: to implement MISS stubs and stub "compiler" that would produce specialized stubs:

function NAMED_LOAD_MISS(t, k, ic) {

var v = LOAD(t, k);

if (t.klass.kind === "fast") {

// Create a load stub that is specialized for a fixed class and key k and

// loads property from a fixed offset.

var stub = CompileNamedLoadFastProperty(t.klass, k);

PatchIC("LOAD", ic, stub);

}

return v;

}

function NAMED_STORE_MISS(t, k, v, ic) {

var klass_before = t.klass;

STORE(t, k, v);

var klass_after = t.klass;

if (klass_before.kind === "fast" &&

klass_after.kind === "fast") {

// Create a store stub that is specialized for a fixed transition between classes

// and a fixed key k that stores property into a fixed offset and replaces

// object's hidden class if necessary.

var stub = CompileNamedStoreFastProperty(klass_before, klass_after, k);

PatchIC("STORE", ic, stub);

}

}

function KEYED_LOAD_MISS(t, k, ic) {

var v = LOAD(t, k);

if (t.klass.kind === "fast" && (typeof k === 'number' && (k | 0) === k)) {

// Create a stub for the fast load from the elements array.

// Does not actually depend on the class but could if we had more complicated

// storage system.

var stub = CompileKeyedLoadFastElement();

PatchIC("KEYED_LOAD", ic, stub);

}

return v;

}

function KEYED_STORE_MISS(t, k, v, ic) {

STORE(t, k, v);

if (t.klass.kind === "fast" && (typeof k === 'number' && (k | 0) === k)) {

// Create a stub for the fast store into the elements array.

// Does not actually depend on the class but could if we had more complicated

// storage system.

var stub = CompileKeyedStoreFastElement();

PatchIC("KEYED_STORE", ic, stub);

}

}

function PatchIC(kind, id, stub) {

this[kind + "$" + id] = stub; // non-strict JS funkiness: this is global object.

}

function CompileNamedLoadFastProperty(klass, key) {

// Key is known to be constant (named load). Specialize index.

var index = klass.getIndex(key);

function KeyedLoadFastProperty(t, k, ic) {

if (t.klass !== klass) {

// Expected klass does not match. Can't use cached index.

// Fall through to the runtime system.

return NAMED_LOAD_MISS(t, k, ic);

}

return t.properties[index]; // Veni. Vidi. Vici.

}

return KeyedLoadFastProperty;

}

function CompileNamedStoreFastProperty(klass_before, klass_after, key) {

// Key is known to be constant (named load). Specialize index.

var index = klass_after.getIndex(key);

if (klass_before !== klass_after) {

// Transition happens during the store.

// Compile stub that updates hidden class.

return function (t, k, v, ic) {

if (t.klass !== klass_before) {

// Expected klass does not match. Can't use cached index.

// Fall through to the runtime system.

return NAMED_STORE_MISS(t, k, v, ic);

}

t.properties[index] = v; // Fast store.

t.klass = klass_after; // T-t-t-transition!

}

} else {

// Write to an existing property. No transition.

return function (t, k, v, ic) {

if (t.klass !== klass_before) {

// Expected klass does not match. Can't use cached index.

// Fall through to the runtime system.

return NAMED_STORE_MISS(t, k, v, ic);

}

t.properties[index] = v; // Fast store.

}

}

}

function CompileKeyedLoadFastElement() {

function KeyedLoadFastElement(t, k, ic) {

if (t.klass.kind !== "fast" || !(typeof k === 'number' && (k | 0) === k)) {

// If table is slow or key is not a number we can't use fast-path.

// Fall through to the runtime system, it can handle everything.

return KEYED_LOAD_MISS(t, k, ic);

}

return t.elements[k];

}

return KeyedLoadFastElement;

}

function CompileKeyedStoreFastElement() {

function KeyedStoreFastElement(t, k, v, ic) {

if (t.klass.kind !== "fast" || !(typeof k === 'number' && (k | 0) === k)) {

// If table is slow or key is not a number we can't use fast-path.

// Fall through to the runtime system, it can handle everything.

return KEYED_STORE_MISS(t, k, v, ic);

}

t.elements[k] = v;

}

return KeyedStoreFastElement;

}It's a lot of code (and comments) but it should be simple to understand given all explanations above: ICs observe and stub compiler/factory produces adapted-specialized stubs [attentive reader can even notice that I could have initialized all keyed store ICs with fast loads from the very start or that it gets stuck in fast state once it enters it].

If we throw all the code we got together and rerun our "benchmark" we'll get very pleasing results:

∮ d8 --harmony quasi-lua-runtime-ic.js points-ic.js 117

This is a factor of 6 speedup compared to our first naïve attempt!

There is never a conclusion to JavaScript VMs optimizations

Hopefully you are reading this part because you have read everything above... I tried to look from a different perspective, that of a JavaScript developer, onto some ideas powering JavaScript engines these days. The more code I was writing the more it felt like a story about blind men and an elephant. Just to give you a feeling of looking into the abyss: V8 has 10 descriptors kinds, 5 elements kinds (+ 9 external elements kinds), ic.cc that contains most of IC state selection logic is more that 2500 LOC and ICs in V8 have more than 2 states (there are uninitialized, premonomorphic, monomorphic, polymorphic, generic states not mentioning special states for keyed load/stores ICs or completely different hierarchy of states for arithmetic ICs), ia32-specific hand written IC stubs take more than 5000 LOC, etc. These numbers only grow as time passes and V8 learns to distinguish&adapt to more and more object layouts. And I am not even touching object model itself (objects.cc 13kLOC), or garbage collector, or optimizing compiler.

Nevertheless I am sure that fundamentals will not change in the foreseeable future and when they do it will be a breakthrough with a loud bang! sound, so you'll notice. Thus I think that this exercise of trying to understand fundamentals by (re)writing them in JavaScript is very-very-very important.

I hope tomorrow or maybe the week after you will stop and shout Eureka! and tell your coworkers why conditionally adding properties to an object in one place of the code can affect performance of some other distant hot loop touching these objects. Because hidden classes, you know, they change!

Want to discuss

contents of this post? Drop me a mail [email protected] or find me on

Mastodon,

X or Bluesky.