Part I: Little substring that could (not).

Few weeks ago a bug was filed against Dart SDK citing “very low performance of String.substring”. Here is a core of microbenchmark developer submitted together with the issue:

// JavaScript version

function test(s){

console.time("substring(js)");

while (s.length > 1) {

s = s.substring(1);

}

console.timeEnd("substring(js)");

}// Dart version

test(s) {

final stopwatch = new Stopwatch()..start();

while (s.length > 1) {

s = s.substring(1);

}

print("substring(Dart): ${stopwatch.elapsedMilliseconds}ms");

}Results are rather bad for Dart version:

$ dart substring.dart benchmarking with string of length 25000 substring(Dart): 244ms benchmarking with string of length 50000 substring(Dart): 949ms benchmarking with string of length 100000 substring(Dart): 3709ms $ node substring.js benchmarking with string of length 25000 substring(js): 2.566ms benchmarking with string of length 50000 substring(js): 2.308ms benchmarking with string of length 100000 substring(js): 2.633ms

Depending on your background you might also be surprised by a non-linear growth in Dart run times: increasing input string size by a factor of \(2\) (\(25000\) to \(50000\)) increases running time by a factor of \(4\) (\(244\) to \(949\) milliseconds).

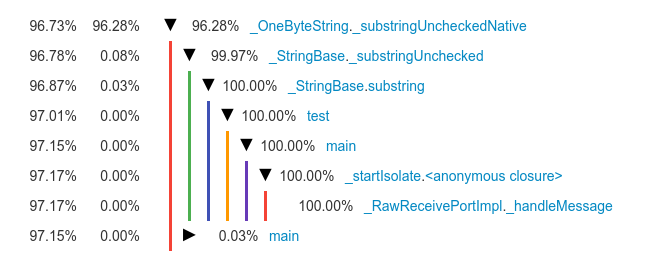

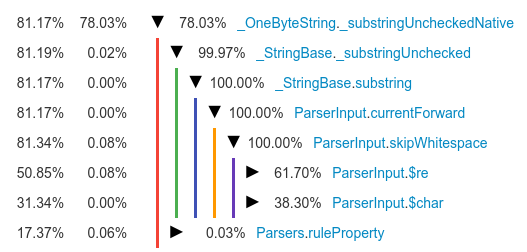

Running benchmark with dart --observe and looking at CPU profile in Observatory reveals an unsuprising picture:

Most of the time is spent doing a substring operation, so why Dart VM’s substring is so much slower than V8’s? They must be implemented completely differently - and indeed they are.

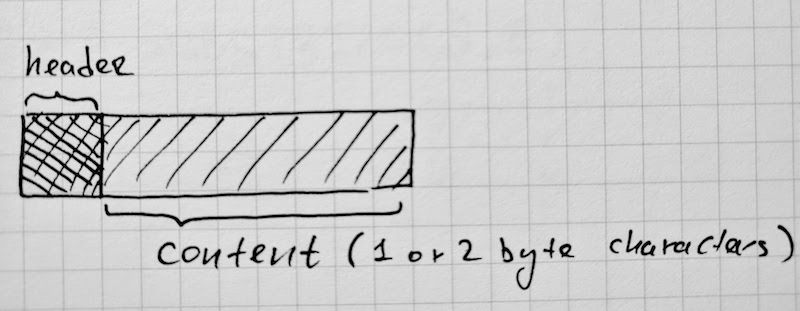

Dart VM implements String.substring(start, end) in a very straightforward manner: it allocates a new String object of length end - start + 1 and copies string contents into this new string. Formally speaking this is an \(O(n)\) implementation - also known as linear time - it requires amount of operations proportional to the length of a substring.

If we take a look at the core of our benchmark then it should become obvious why running times exhibit quadratic growth:

while (s.length > 1) {

s = s.substring(1);

}If we assuming that initial length of the string s is \(N\) the the first iteration of the loop creates a substring of length \(N - 1\), next iteration creates substring of length \(N - 2\) and so on, until the last iteration creates a substring of length \(1\). This means the loop requires

operations, which is proportional to \(N^2\).

[If you have never encountered this sequence before I suggest to stop and think for a bit how a formula for its sum is derived. Solution’s simplicity and elegance might provide a welcomed retreat from fighting Webpack configs. The Prince of Mathematics Carl Friedrich Gauss managed to figure it out when he was 8 - though obviously we would never know what he would do facing modern JavaScript ecosystem.]

The \(O(N^2)\) complexity of the above loop is precisely the reason why it’s not a good idea to iterate a string by slicing away processed pieces, unless of course your runtime does “a bit” of magic internally and optimizes for this particular pattern… unsurprisingly V8 does.

If we take a look into V8 sources we discover a somewhat intimidating zoo of different string representations, each optimizing for some particular use case (indexing, concatenation, slicing):

// The String abstract class captures JavaScript string values:

//

// Ecma-262:

// 4.3.16 String Value

// A string value is a member of the type String and is a finite

// ordered sequence of zero or more 16-bit unsigned integer values.

//

// All string values have a length field.

class String: public Name {

// ...

};

// The SeqString abstract class captures sequential string values.

class SeqString: public String {

// ...

};

// The OneByteString class captures sequential one-byte string objects.

// Each character in the OneByteString is an one-byte character.

class SeqOneByteString: public SeqString {

// ...

};

// The TwoByteString class captures sequential unicode string objects.

// Each character in the TwoByteString is a two-byte uint16_t.

class SeqTwoByteString: public SeqString {

// ...

};

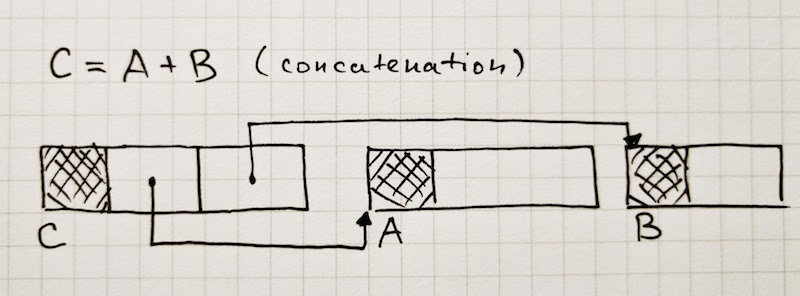

// The ConsString class describes string values built by using the

// addition operator on strings. A ConsString is a pair where the

// first and second components are pointers to other string values.

// One or both components of a ConsString can be pointers to other

// ConsStrings, creating a binary tree of ConsStrings where the leaves

// are non-ConsString string values. The string value represented by

// a ConsString can be obtained by concatenating the leaf string

// values in a left-to-right depth-first traversal of the tree.

class ConsString: public String {

// ...

};

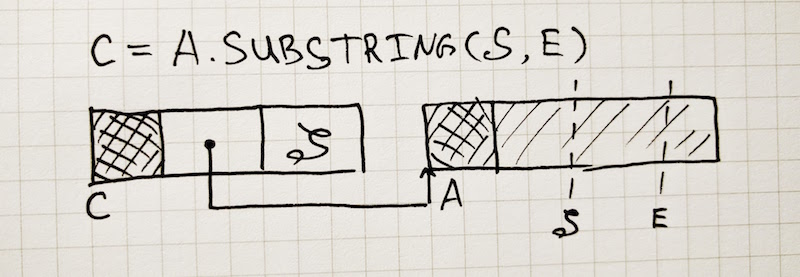

// The Sliced String class describes strings that are substrings of another

// sequential string. The motivation is to save time and memory when creating

// a substring. A Sliced String is described as a pointer to the parent,

// the offset from the start of the parent string and the length. Using

// a Sliced String therefore requires unpacking of the parent string and

// adding the offset to the start address. A substring of a Sliced String

// are not nested since the double indirection is simplified when creating

// such a substring.

// Currently missing features are:

// - handling externalized parent strings

// - external strings as parent

// - truncating sliced string to enable otherwise unneeded parent to be GC'ed.

class SlicedString: public String {

// ...

};

// The ExternalString class describes string values that are backed by

// a string resource that lies outside the V8 heap. ExternalStrings

// consist of the length field common to all strings, a pointer to the

// external resource. It is important to ensure (externally) that the

// resource is not deallocated while the ExternalString is live in the

// V8 heap.

//

// The API expects that all ExternalStrings are created through the

// API. Therefore, ExternalStrings should not be used internally.

class ExternalString: public String {

// ...

};

// The ExternalOneByteString class is an external string backed by an

// one-byte string.

class ExternalOneByteString : public ExternalString {

// ...

};

// The ExternalTwoByteString class is an external string backed by a UTF-16

// encoded string.

class ExternalTwoByteString: public ExternalString {

// ...

};Whenever you see a string value in your JavaScript code - it can actually be backed by any of those representations, runtime is able to operate with them interchangeably and even can go from one representation to another dynamically if that improves performance of some operation.

[Other JavaScript runtimes have similarly convoluted representation hierarchies spawned by benchmark races and desire to optimize for common usage patterns. See SpiderMonkey’s String.h, JSC’s JSString.h and *String.h files in Chakra’s sources]

Understanding differences between different string representations used by different JS runtimes is usually a key to understanding why your string manipulation code performs in a certain way. For example we could digress and discuss why

function strange() {

var s = "01234567891011121314";

for (var i = 0; i < 100000; i++) {

s += s[Math.floor(s.length / 2)];

}

return s;

}runs 60 times faster in SpiderMonkey than in V8 - but unfortunately that’s beyond the scope of this post.

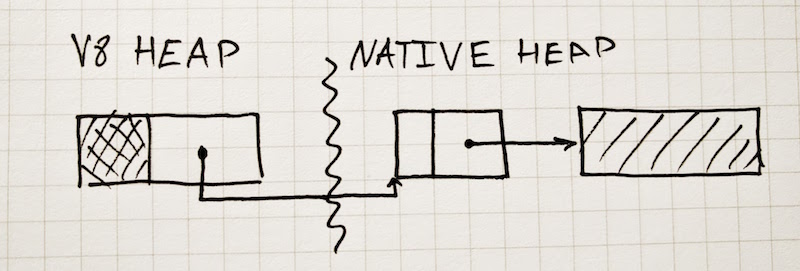

Lets return back to the String.prototype.substring microbenchmark in question. Cutting through the layers of C++ and assembly we would eventually arrive to the code implementing substring operation:

// Note: this a cleaned up version of the original V8 code with some

// unimportant details removed for readablity.

Handle<String> Factory::NewProperSubString(Handle<String> str,

int begin,

int end) {

// If string is a cons-string produced as a result of concatenations

// flatten it to have a flat representation.

str = String::Flatten(str);

int length = end - begin;

if (length < SlicedString::kMinLength /* 13 */) {

// If resulting substring is small then simply allocate a new sequential

// string and fill it with characters.

if (str->IsOneByteRepresentation()) {

Handle<SeqOneByteString> result =

NewRawOneByteString(length).ToHandleChecked();

uint8_t* dest = result->GetChars();

String::WriteToFlat(*str, dest, begin, end);

return result;

} else {

Handle<SeqTwoByteString> result =

NewRawTwoByteString(length).ToHandleChecked();

uc16* dest = result->GetChars();

String::WriteToFlat(*str, dest, begin, end);

return result;

}

}

// Resulting substring is large enough to warrant sliced-string allocation.

// Instead of allocating sequential string and copying substring characters

// allocate a SlicedString object that contains a pointer to the

// original string, substring start offset and substring length.

int offset = begin;

// If input string is a SlicedString itself unwrap it.

if (str->IsSlicedString()) {

Handle<SlicedString> slice = Handle<SlicedString>::cast(str);

str = slice->parent();

offset += slice->offset();

}

// Create a slice.

Handle<SlicedString> slice = New<SlicedString>(...);

slice->set_hash_field(String::kEmptyHashField);

slice->set_length(length);

slice->set_parent(*str);

slice->set_offset(offset);

return slice;

}[With V8 nothing is ever implemented just in a single place, so lost souls searching for substring implementation might also find themselves digging into CodeStubAssembler::SubString which constructs TurboFan graph that would be compiled down to machine code to serve as the SubString stub - which essentially implements fast paths for the C++ logic above.]

Translating the C++ logic to Dart we would get something like this:

class StringSlice /* implements String */ {

final String parent;

final int offset;

final int length;

StringSlice(this.parent, this.offset, this.length);

static substring(str, start, [end]) {

if (end == null) {

end = str.length;

} else if (end > str.length) {

throw "range error: end ${end} is greater than string length ${str.length}";

}

if (start < 0 || start >= end) {

throw "range error: start ${start} is out of range [0, ${end})";

}

final length = end - start;

if (str is StringSlice) {

start += str.offset;

str = str.parent;

}

return new StringSlice(str, start, length);

}

}

test(s) {

final stopwatch = new Stopwatch()..start();

while (s.length > 1) {

s = StringSlice.substring(s, 1);

}

print("substring(Dart): ${stopwatch.elapsedMilliseconds}ms");

}$ dart substring.dart benchmarking with string of length 25000 substring(Dart): 3ms benchmarking with string of length 50000 substring(Dart): 3ms benchmarking with string of length 100000 substring(Dart): 1ms

This is what JavaScript version is approximately doing and it explains why we don’t observe quadratic complexity on the microbenchmark: roughly speaking substring operations take constant amount of time (assuming that input string is flat and disregarding memory management overhead) and thus instead of

\[(N - 1) + (N - 2) + \ldots + 1 = N \times \frac{N - 1}{2} \approx O(N^2)\]you get

\[C + C + \ldots + C = C \times N \approx O(N)\]Given such a drastic performance improvement why would not we implement a similar optimization in Dart VM? Well, this substring optimization comes with a dangerous trap built in: it leads to surprising memory leaks:

function process(str) {

var small20CharToken = str.substring(0, 20);

return {token: small20CharToken};

}

var obj = process(gigantic10GbString);Counterintuitively obj above retains the whole 10Gb input string instead of a small 20 character token - because this token is internally represented as a SlicedString that points back to the source string. This might seem like a contrived example but leaks like this do tend to happen in the real world: here is a three.js issue describing how they had to work around this issue, here is a blog post from somebody who had to hunt for this leak in production. Eagerness of a runtime to fall over itself and make your code faster with clever hidden optimizations has an ugly side too. Issue 2869 tracks progress of fixing this on the V8 side, but nothing has really happened since 2013, probably because the only simple and robust solution is to remove sliced strings altogether. Interestingly that’s precisely what Java did - they used to implement String.substring in \(O(1)\) time by reusing parent String’s char[] storage for the substring object but that lead to memory leaks and was eventually removed in 2012. V8 history with string slices is even more curious: originally V8 had them, then removed them in 2009, then added it back in 2011.

This all is somewhat bad news for the original Dart SDK bug which prompted this trip down the memory lane. Indeed Dart VM is unlikely to implement substring optimization through sliced-strings. That’s why I decided to probe: why exactly they are measuring substring performance?

Part II: Enter less_dart.

Turns out that bug was prompted by their investigation into the slowness of less_dart - which is a port of less.js from JavaScript to Dart.

Looking at less_dart benchmark in the Observatory reveals the following picture:

That is Less parser is doing exactly what I would not recommend - iterating through the input string using substring operation. Looking into the source reveals the following code and the reason for using substring becomes obvious:

$re(RegExp reg, [int index]) {

if (i > currentPos) {

current = current.substring(i - currentPos);

currentPos = i;

}

Match m = reg.firstMatch(current);

if (m == null) return null;

// ... skipped ...

}[Code is ported word-for-word from JavaScript so exactly the same code exists in JavaScript version where its, ahm, suboptimality is hidden by the helpful JavaScript runtime]

Authors of Less decided to parse input using regular expressions instead of writing custom lexer, however in pre-ES6 world lexing with RegExp-s was convoluted by the fact that you could not take a regular expression and easily check if it matches at the given position, which is what lexer needs to do as it advances through the string and breaks it into tokens.

function Lexer(str) {

this.str = str;

this.idx = 0;

}

Lexer.prototype.nextToken = function () {

if (this.idx == this.str.length)

return "eof";

else if (this.match(/\d+(?!\w)/))

return "number";

else if (this.match(/[a-zA-Z_]\w*/)) {

// note: names can't start with a digit

return "name";

} else if (this.match(/\s+/))

return "space";

else

throw "unexpected token";

};

// Try to match the given regexp at the current

// position (this.index) in the string.

// If match succeeds then advance position in the

// string past it and return the match object.

// Otherwise return null.

Lexer.prototype.match = function (re) {

// ???

};match can be easily implemented in any modern JavaScript interpreter that supports sticky RegExp flag introduced in ES6:

Lexer.prototype.match = function (re) {

re.lastIndex = this.idx;

var m = re.exec(this.str);

if (m != null) {

this.idx = re.lastIndex;

}

return m;

};

// Note: all regular expressions now need to have

// sticky bit set.

Lexer.prototype.nextToken = function () {

if (this.idx == this.str.length)

return "eof";

else if (this.match(/\d+(?!\w)/y))

return "number";

else if (this.match(/[a-zA-Z]\w*/y))

return "name";

else if (this.match(/\s+/y))

return "space";

else

throw "unexpected token";

};[The flag y is apparently named after yylex which is part of the Lex API (not to be confused with Lexx which is a spaceship based on the organic technology which is far beyond even things included into ES7). The name sticky in turn was apparently chosen because it ends with y.]

However what is the way to implement match in a pre-ES6 JS engine? A very naive approach would be to do something like this:

Lexer.prototype.match = function (re) {

re.lastIndex = this.idx;

var m = re.exec(this.str);

// No match at all or match at a wrong

// position

if (m === null ||

m.index !== this.idx) {

return null;

}

this.idx = re.lastIndex;

return m;

};

// Note: all regular expressions now need to have

// global bit set otherwise lastIndex will be

// ignored.

Lexer.prototype.nextToken = function () {

if (this.idx == this.str.length)

return "eof";

else if (this.match(/\d+(?!\w)/g))

return "number";

else if (this.match(/[a-zA-Z]\w*/g))

return "name";

else if (this.match(/\s+/g))

return "space";

else

throw "unexpected token";

};This however is extremely inefficient because calling match(/\d+/g) would essentially search from this.idx forward for the first sequence of digits and then discard the match unless it occurred at this.idx.

A person with a bit more insight into RegExp features might come up with the following optimization:

// Note: all regexps have irrefutable pattern

// as an alternative "...|()" this guarantees

// that regexp engine won't attempt to match

// this expression at a different position because

// irrefutable pattern always matches.

Lexer.prototype.nextToken = function () {

if (this.idx == this.str.length)

return "eof";

else if (this.match(/\d+(?!\w)|()/g))

return "number";

else if (this.match(/[a-zA-Z]\w*|()/g))

return "name";

else if (this.match(/\s+|()/g))

return "space";

else

throw "unexpected token";

};

Lexer.prototype.match = function (re) {

re.lastIndex = this.idx;

var m = re.exec(this.str);

// No match at all or an empty match.

if (m === null || m[0] === "") {

return null;

}

this.idx = re.lastIndex;

return m;

};However a much more common and straightforward way to implement match would be to use substring and anchored regexps:

Lexer.prototype.match = function (re) {

var m = re.exec(this.str);

if (m !== null) return null;

// Slice away consumed part of the string.

this.str = this.str.substring(m[0].length);

return m;

};

// Note: all regular expressions now need to

// be anchored at the start.

Lexer.prototype.nextToken = function () {

if (this.str.length === 0)

return "eof";

else if (this.match(/^\d+(?!\w)/))

return "number";

else if (this.match(/^[a-zA-Z]\w*/))

return "name";

else if (this.match(/^\s+/))

return "space";

else

throw "unexpected token";

};This is exactly the code we see in the less.js and less_dart - fortunately for less.js V8 runtime implements String.prototype.substring as a \(O(1)\) operation, unfortunately for less_dart Dart VM does not.

What Dart VM does implement is RegExp.matchAsPrefix method - which essentially performs a sticky match of the given regular expression at the given position. Hooray! ☺

However when I did necessary changes to the less_dart code I discovered that it actually became several times slower. Hmm. ☹

It turns out there was a little TODO inside VM’s RegExp implementation:

Match matchAsPrefix(String string, [int start = 0]) {

// ...

// Inefficient check that searches for a later match too.

// Change this when possible.

List<int> list = _ExecuteMatch(string, start);

if (list == null) return null;

if (list[0] != start) return null;

return new _RegExpMatch(this, string, list);

}Obviously the solution was to fix VM by implementing RegExp.matchAsPrefix in the same way V8 implements sticky flag - which is rather simple because Dart VM is using essentially the same regexp engine as one in V8 called Irregexp.

[Maybe we should have called Dart VM port IrIrRegexp because instead of translating RegExp specific intermediate representation (IR) down to the machine code Dart VM translates it further into our machine independent IR and let the generic compiler pipeline take care of it. This allowed us to incorporate Irregexp into Dart VM without porting any machine specific regexp related backend code.]

So I just went and talked to Erik Corry who was one of the minds behind original Irregexp about his implementation of sticky flag. Then I just ported it to Dart VM… and found and fixed a very minor bug in V8’s sticky implementation while doing that.

With RegExp.matchAsPrefix implemented in the efficient way my fixes in the less_dart gave an expected performance improvements brining less_dart and less.js neck to neck with each other.

Part III: The trap of RegExps.

I could have finished my post on this positive note, but I would like to circle back to the common idea of using regexps to tokenize the source code.

A very important thing to realize here is that while regular expressions are certainly a convenient way to lex - they are in no way the most efficient way to do it - there are simply too many abstractions layers involved.

If we take our previous attempts at tokenizing with regexps and benchmark them on a simple string like ("aaaaa aaaa ".repeat(50) + "10 ").repeat(10000) then

we will see the following performance numbers:

# Naive tokenizer that just uses global regexps with lastIndex. $ node tokenize-global.js processed 2020001 tokens in 987ms # Tokenizer that is using a global regexps with an irrefutable pattern # to prevent searching for regexp match forward. $ node tokenize-global-irrefutable.js processed 2020001 tokens in 471ms # Tokenizer that uses anchored regexps and substring to slice # away the processed part of the string. $ node tokenize-substring.js processed 2020001 tokens in 393ms # Tokenizer that uses sticky regexps. $ node tokenize-sticky.js processed 2020001 tokens in 295ms

Can you go any faster? Lets erase abstraction barriers and go full manual:

function Lexer(str) {

this.str = str; // Input string

this.idx = 0; // Current position within the input.

this.tok = null; // Last parsed token type (number, name, space)

this._tokStart = this._tokEnd = 0; // Last parsed token position.

}

// Lazy getter for the token value - to avoid allocating substrings

// when not needed.

Object.defineProperty(Lexer.prototype, "val", {

get: function () {

return this.str.substring(this._tokStart, this._tokEnd);

}

});

function isDigit(ch) {

return 48 /* 0 */ <= ch && ch <= 57 /* 9 */;

}

function isAlpha(ch) {

ch &= ~32;

return 65 /* A */ <= ch && ch <= 90 /* Z */;

}

function isIdent(ch) {

return isAlpha(ch) ||

isDigit(ch) ||

ch === 95 /* _ */

}

function isSpace(ch) {

return ch === 9 /* \t */ ||

ch === 10 /* \n */ ||

ch === 13 /* \r */ ||

ch === 32 /* space */;

}

Lexer.prototype.nextToken = function () {

if (this.idx >= this.str.length) {

return "eof";

}

this._tokStart = this.idx;

var ch = this.str.charCodeAt(this.idx++);

if (isDigit(ch)) {

while (this.idx < this.str.length &&

isDigit(this.str.charCodeAt(this.idx))) {

this.idx++;

}

if (this.idx < this.str.length && isIdent(this.str.charCodeAt(this.idx))) {

throw "unexpected token";

}

this.tok = "number";

} else if (isAlpha(ch) || ch === 95) {

while (this.idx < this.str.length &&

isIdent(this.str.charCodeAt(this.idx))) {

this.idx++;

}

this.tok = "name";

}

else if (isSpace(ch)) {

while (this.idx < this.str.length &&

isSpace(this.str.charCodeAt(this.idx))) {

this.idx++;

}

this.tok = "space";

}

else

throw `unexpected token '${ch}'`;

this._tokEnd = this.idx;

return this.tok;

};Benchmarking this tokenizer with the very same benchmark I used for others:

function benchmark() {

var seq = ("aaaaa aaaa ".repeat(50) + "10 ").repeat(10000);

var l = new Lexer(seq);

var start = Date.now();

var cnt = 0;

do {

var tok = l.nextToken();

cnt++;

} while (tok != "eof");

var end = Date.now();

console.log(`processed ${cnt} tokens in ${end - start}ms`);

}reveals the following result:

$ node tokenize-manual.js processed 2020001 tokens in 50ms

The main thing this demonstrates - is that you program can get much faster if it’s doing less work. For example our manual tokenizer simply glides through the string without allocating any substring objects for tokens. However if we add var val = l.val; inside the benchmark loop to force this meaningless allocation we will still see performance that is much better than our RegExp based parsers:

$ node tokenize-manual.js processed 2020001 tokens in 98ms

For the sake of completeness here is the same kind of lexer benchmark in Dart:

class Lexer {

final String str; /// Input string.

int idx = 0; /// Current position within the str.

Lexer(this.str);

Token tok; /// Last processed token type.

/// Last processed token value.

String get val => str.substring(_tokStart, _tokEnd);

/// Beginning and end positions of the last processed token.

var _tokStart = 0;

var _tokEnd = 0;

Token nextToken() {

if (idx == str.length) return Token.End;

_tokStart = idx;

final ch = advance();

if (isDigit(ch)) {

while (isDigit(currentChar)) idx++;

if (isIdent(currentChar)) {

throw "unexpected token";

}

tok = Token.Number;

} else if (isAlpha(ch) || ch == _) {

while (isIdent(currentChar)) idx++;

tok = Token.Name;

} else if (isSpace(ch)) {

while (isSpace(currentChar)) idx++;

tok = Token.Space;

} else {

throw "unexpected token";

}

_tokEnd = idx;

return tok;

}

int advance() => str.codeUnitAt(idx++);

int get currentChar => idx < str.length ? str.codeUnitAt(idx) : 0;

static final ZERO = '0'.codeUnitAt(0);

static final NINE = '9'.codeUnitAt(0);

static final A = 'A'.codeUnitAt(0);

static final Z = 'Z'.codeUnitAt(0);

static final _ = '_'.codeUnitAt(0);

static final SPACE = ' '.codeUnitAt(0);

static final LF = '\n'.codeUnitAt(0);

static final CR = '\r'.codeUnitAt(0);

static final TAB = '\t'.codeUnitAt(0);

static isDigit(ch) => ZERO <= ch && ch <= NINE;

static isAlpha(ch) {

ch = ch & ~32;

return (A <= ch && ch <= Z);

}

static isSpace(ch) => ch == SPACE || ch == LF || ch == CR || ch == TAB;

static isIdent(ch) => isAlpha(ch) || isDigit(ch) || ch == _;

}

enum Token {

Number, Name, Space, End

}

benchmark() {

var seq = ("aaaaa aaaa " * 50 + "10 ") * 10000;

var l = new Lexer(seq);

final stopwatch = new Stopwatch()..start();

var tok, val;

var cnt = 0;

do {

tok = l.nextToken();

val = l.val; // Force substring allocation.

cnt++;

} while (tok != Token.End);

print('processed ${cnt} tokens in ${stopwatch.elapsedMilliseconds}ms');

return val;

}Dart VM does respectable job of this code:

$ dart tokenize.dart processed 2020001 tokens in 67ms

So overall performance advice can be summarized as follows:

- When using RegExps for lexing use sticky ones in node and use

RegExp.matchAsPrefixin Dart VM. - Strongly consider writing your lexer by hand instead of using regular expressions.

- The less work your program is doing the faster it is. The less abstraction layers are involved the simpler it is to establish how much work your program is actually doing and decrease the amount.

Want to discuss

contents of this post? Drop me a mail [email protected] or find me on

Mastodon,

X or Bluesky.